by Mark Dickens

You are welcome to quote any material from this website in an article or research paper, but please give the appropriate URL of the webpage you are quoting from. Thank you!

by Mark Dickens

You are welcome to quote any material from this website in an article or research paper, but please give the appropriate URL of the webpage you are quoting from. Thank you!

Driving

along the main road which connects the airport to downtown Tashkent,

the

capital of Uzbekistan, we passed under row upon row of colored lights

strung

out overhead, remnants of the recent celebration of the third

anniversary

of Mustaqillik

("Independence"), a commemoration of Uzbekistan’s

emergence as an independent member of the world community on September

1, 1991. On either side of the road, men in traditional black and white

skullcaps and women in multicolored atlas silk dresses and

bright

head scarves were walking home from the market or waiting for buses.

The

monolithic concrete apartment and office buildings lining the road,

some

with small satellite dishes perched on their balconies, reminded us

that

we were in a cultural intertidal zone, one of those places where the

East

and the West spill over into each other’s world.

Driving

along the main road which connects the airport to downtown Tashkent,

the

capital of Uzbekistan, we passed under row upon row of colored lights

strung

out overhead, remnants of the recent celebration of the third

anniversary

of Mustaqillik

("Independence"), a commemoration of Uzbekistan’s

emergence as an independent member of the world community on September

1, 1991. On either side of the road, men in traditional black and white

skullcaps and women in multicolored atlas silk dresses and

bright

head scarves were walking home from the market or waiting for buses.

The

monolithic concrete apartment and office buildings lining the road,

some

with small satellite dishes perched on their balconies, reminded us

that

we were in a cultural intertidal zone, one of those places where the

East

and the West spill over into each other’s world.

Despite

the long flight, we were not suffering from jet lag. When our American

friends invited us to attend a tui (party) at the home of

their

friend Zahiriddin on our first night in Uzbekistan, we jumped at the

opportunity.

Uzbeks pride themselves on their hospitality and are quick to invite

foreigners

to join them for a meal. This particular tui

was a celebration of

the seventh day after a wedding. The bride met us at the door in a

special

wedding costume and veil and we were ushered into the dining room,

where

we sat down at a table spread with an abundance of food:

shashlik (kebabs),

samsa

(meat

pies), nan (round flat bread), shorba (soup), grapes,

apples,

pomegranates, pistachios, almonds, sweets, edible icing-sugar flowers,

champagne, tea, mineral water, and the ever-present vodka.

Despite

the long flight, we were not suffering from jet lag. When our American

friends invited us to attend a tui (party) at the home of

their

friend Zahiriddin on our first night in Uzbekistan, we jumped at the

opportunity.

Uzbeks pride themselves on their hospitality and are quick to invite

foreigners

to join them for a meal. This particular tui

was a celebration of

the seventh day after a wedding. The bride met us at the door in a

special

wedding costume and veil and we were ushered into the dining room,

where

we sat down at a table spread with an abundance of food:

shashlik (kebabs),

samsa

(meat

pies), nan (round flat bread), shorba (soup), grapes,

apples,

pomegranates, pistachios, almonds, sweets, edible icing-sugar flowers,

champagne, tea, mineral water, and the ever-present vodka.

The

next morning, we awoke to the sound of a canary singing and roosters

crowing.

This was our first day of exploring Tashkent, the capital. With a

population

of about 2.5 million, it was the fourth largest city in the former

Soviet

Union and it is the most important center in Central Asia today. As we

headed out to see the city, we became more aware of the changes this

country

is going through. In the minds of many, this time of transition is a

rebirth

of the Uzbek people, a sentiment clearly portrayed in the state seal of

the new republic, prominently displayed on everything from government

buildings

to plastic shopping bags. Against a backdrop of the sun rising over the

Tien Shan mountains and the twin rivers of Uzbekistan, the Syr Darya

and

the Amu Darya, a phoenix spreads its wings. Rising from the ashes of

Communism,

this ancient symbol of reincarnation proclaims the hope that Uzbekistan

will go on to recapture some of the greatness of the empires which have

sprung up in Central Asia over the past two millennia. On billboards

and

neon signs, this sentiment is echoed in the words of President Islam

Karimov:

Ozbekistan

kelajagi buyuk dawlat! -- Uzbekistan’s future: a great country!

The

next morning, we awoke to the sound of a canary singing and roosters

crowing.

This was our first day of exploring Tashkent, the capital. With a

population

of about 2.5 million, it was the fourth largest city in the former

Soviet

Union and it is the most important center in Central Asia today. As we

headed out to see the city, we became more aware of the changes this

country

is going through. In the minds of many, this time of transition is a

rebirth

of the Uzbek people, a sentiment clearly portrayed in the state seal of

the new republic, prominently displayed on everything from government

buildings

to plastic shopping bags. Against a backdrop of the sun rising over the

Tien Shan mountains and the twin rivers of Uzbekistan, the Syr Darya

and

the Amu Darya, a phoenix spreads its wings. Rising from the ashes of

Communism,

this ancient symbol of reincarnation proclaims the hope that Uzbekistan

will go on to recapture some of the greatness of the empires which have

sprung up in Central Asia over the past two millennia. On billboards

and

neon signs, this sentiment is echoed in the words of President Islam

Karimov:

Ozbekistan

kelajagi buyuk dawlat! -- Uzbekistan’s future: a great country!

Uzbekistan

is one of the newest independent countries in the world, born in the

wake

of the collapse of the USSR. This nation of approximately 23 million is

the size of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maine, and Vermont combined

(nearly

175,000 sq. mi.) and is located just north of Afghanistan, with

Tashkent

at approximately the same latitude as New York City. In many ways, it

is

the richest of the five Central Asian republics which split away from

Moscow

in the summer of 1991. It has the world’s largest gold mine and is the

fourth largest producer of cotton. There are also rich deposits of gas,

oil, and coal, as well as an abundance of agricultural products.

Uzbekistan

is one of the newest independent countries in the world, born in the

wake

of the collapse of the USSR. This nation of approximately 23 million is

the size of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maine, and Vermont combined

(nearly

175,000 sq. mi.) and is located just north of Afghanistan, with

Tashkent

at approximately the same latitude as New York City. In many ways, it

is

the richest of the five Central Asian republics which split away from

Moscow

in the summer of 1991. It has the world’s largest gold mine and is the

fourth largest producer of cotton. There are also rich deposits of gas,

oil, and coal, as well as an abundance of agricultural products.

When

it became evident that the Soviet Union was not going to recover in the

aftermath of the 1991 coup, President Karimov seized the opportunity to

declare Uzbekistan an independent nation and changed the name of his

Communist

Party to the People’s Democratic Party. Despite the fact that Karimov

and

his fellow ex-Communists are still in power, they have moved quickly to

dissociate themselves from the old regime. All over Uzbekistan,

monuments

from the Soviet days that were not Uzbek enough are being torn down and

replaced by new ones.

When

it became evident that the Soviet Union was not going to recover in the

aftermath of the 1991 coup, President Karimov seized the opportunity to

declare Uzbekistan an independent nation and changed the name of his

Communist

Party to the People’s Democratic Party. Despite the fact that Karimov

and

his fellow ex-Communists are still in power, they have moved quickly to

dissociate themselves from the old regime. All over Uzbekistan,

monuments

from the Soviet days that were not Uzbek enough are being torn down and

replaced by new ones.

As

is the case elsewhere in the former USSR, Lenin and Marx have been

removed

from their pedestals and relegated to the junk piles of history. In

Tashkent,

a large globe with a map of Uzbekistan on it has been erected where the

founder of the Soviet Union once stood, while Marx’s place has been

taken

by Timur (1336-1405), known in the West as Tamerlane, the great

fourteenth

century conqueror whose empire reached as far as Anatolia, India and

the

gates of Moscow. Timur is gradually being elevated as a national hero

and

a model of Uzbek greatness, since his imperial capital of Samarkand is

located in modern-day Uzbekistan.

As

is the case elsewhere in the former USSR, Lenin and Marx have been

removed

from their pedestals and relegated to the junk piles of history. In

Tashkent,

a large globe with a map of Uzbekistan on it has been erected where the

founder of the Soviet Union once stood, while Marx’s place has been

taken

by Timur (1336-1405), known in the West as Tamerlane, the great

fourteenth

century conqueror whose empire reached as far as Anatolia, India and

the

gates of Moscow. Timur is gradually being elevated as a national hero

and

a model of Uzbek greatness, since his imperial capital of Samarkand is

located in modern-day Uzbekistan.

From

Tashkent we traveled by bus to fabled Samarkand, a city of over half a

million about 290 kilometers to the southwest. After a four hour bus

ride,

during which we chatted with Kamar and Ulughbek, two young men who

worked

as "cowboys," we finally arrived in Timur’s ancient capital. Our first

stop was the Gur Emir, the conqueror’s mausoleum. The tomb, completed

in

1404, is an impressive edifice topped by a ribbed, azure-colored dome.

According to historical accounts of the day, it was rebuilt in ten

days,

after Timur complained that it was too low.

From

Tashkent we traveled by bus to fabled Samarkand, a city of over half a

million about 290 kilometers to the southwest. After a four hour bus

ride,

during which we chatted with Kamar and Ulughbek, two young men who

worked

as "cowboys," we finally arrived in Timur’s ancient capital. Our first

stop was the Gur Emir, the conqueror’s mausoleum. The tomb, completed

in

1404, is an impressive edifice topped by a ribbed, azure-colored dome.

According to historical accounts of the day, it was rebuilt in ten

days,

after Timur complained that it was too low.

From

the Gur Emir, it is only a short walk to the Registan, the grandiose

ensemble

of three madrassahs (the Shir Dor, the Tillya Kari, and the

Ulugh

Bek) that occupies the central square in the city. These seminaries,

built

in the 15th and 17th centuries, stand on the former site of Timur’s

grand

bazaar, where he used to display the heads of his victims on top of

tall

spikes. The buildings are an impressive collage of fluted cupolas,

minarets

covered with angular calligraphy, delicate gold leaf-covered interior

domes,

and mosaics of flowers, stars, lions and suns.

From

the Gur Emir, it is only a short walk to the Registan, the grandiose

ensemble

of three madrassahs (the Shir Dor, the Tillya Kari, and the

Ulugh

Bek) that occupies the central square in the city. These seminaries,

built

in the 15th and 17th centuries, stand on the former site of Timur’s

grand

bazaar, where he used to display the heads of his victims on top of

tall

spikes. The buildings are an impressive collage of fluted cupolas,

minarets

covered with angular calligraphy, delicate gold leaf-covered interior

domes,

and mosaics of flowers, stars, lions and suns.

Two

more architectural monuments worth seeing in Samarkand are the Bibi

Khanum

Mosque and the Shah-i-Zinda complex. The former is an immense,

cathedral-sized

edifice built by Timur for his favorite wife. Unfortunately, it is now

in serious disrepair as a result of the cumulative effect of poor

construction

methods, earthquakes, and the conqueror’s penchant for trooping his war

elephants through the interior. A gigantic crane and scaffolding attest

to the ongoing restoration work underway at this and other monuments

around

the country.

Two

more architectural monuments worth seeing in Samarkand are the Bibi

Khanum

Mosque and the Shah-i-Zinda complex. The former is an immense,

cathedral-sized

edifice built by Timur for his favorite wife. Unfortunately, it is now

in serious disrepair as a result of the cumulative effect of poor

construction

methods, earthquakes, and the conqueror’s penchant for trooping his war

elephants through the interior. A gigantic crane and scaffolding attest

to the ongoing restoration work underway at this and other monuments

around

the country.

The

Shah-i-Zinda complex is a grouping of tombs on the site of the old city

of Afrasiab, a ten minute walk from Bibi Khanum. The group of mausolea

derives its name, meaning "The Living King," from the legend of Qasim

ibn

Abbas, supposedly the cousin of Muhammad himself, who was beheaded by

locals

while at prayer. He subsequently picked up his head, and jumped into a

well, where he lives on. It is still a major pilgrimage site for

Muslims

in Central Asia.

The

Shah-i-Zinda complex is a grouping of tombs on the site of the old city

of Afrasiab, a ten minute walk from Bibi Khanum. The group of mausolea

derives its name, meaning "The Living King," from the legend of Qasim

ibn

Abbas, supposedly the cousin of Muhammad himself, who was beheaded by

locals

while at prayer. He subsequently picked up his head, and jumped into a

well, where he lives on. It is still a major pilgrimage site for

Muslims

in Central Asia.

Our

next stop was Bukhara, located 270 kilometers due west of Samarkand, a

city of a quarter million. Along with Samarkand, "Bukhara the Holy" was

one of the foremost cities of learning in the Muslim world in the tenth

and eleventh centuries and was home to such great minds as Avicenna

(980-1037),

whose Canon of Medicine was the basic medical text in Europe

until

the Renaissance. A proverb of the time stated: "In all other parts of

the

world, light descends upon the earth; from holy Bukhara, it ascends."

Arriving

in the late afternoon, we ventured into the old city to photograph the

effects of the setting sun on the domes of Bukhara. The orange tint of

the sunset on stone walls, combined with the rich blues of the cupolas

and the sky, made one feel that light had not stopped ascending from

the

holy city.

Our

next stop was Bukhara, located 270 kilometers due west of Samarkand, a

city of a quarter million. Along with Samarkand, "Bukhara the Holy" was

one of the foremost cities of learning in the Muslim world in the tenth

and eleventh centuries and was home to such great minds as Avicenna

(980-1037),

whose Canon of Medicine was the basic medical text in Europe

until

the Renaissance. A proverb of the time stated: "In all other parts of

the

world, light descends upon the earth; from holy Bukhara, it ascends."

Arriving

in the late afternoon, we ventured into the old city to photograph the

effects of the setting sun on the domes of Bukhara. The orange tint of

the sunset on stone walls, combined with the rich blues of the cupolas

and the sky, made one feel that light had not stopped ascending from

the

holy city.

Unlike

Samarkand, which has a few large monuments spread throughout the city,

the heart of Bukhara is like a living museum. Walking through the

center

of the city, one is surrounded by history. Towering over the

surrounding

madrassahs,

the Kalyan Minaret, built in 1127, is all that remains of the city from

before the time of Jenghiz Khan. After climbing the 105 steps to the

top,

we were able to see a magnificent view of the city. Despite its

reputation

as "the Tower of Death," Maksuma, our English-speaking guide, told us

that

only one person had been thrown from the top of the minaret.

Unlike

Samarkand, which has a few large monuments spread throughout the city,

the heart of Bukhara is like a living museum. Walking through the

center

of the city, one is surrounded by history. Towering over the

surrounding

madrassahs,

the Kalyan Minaret, built in 1127, is all that remains of the city from

before the time of Jenghiz Khan. After climbing the 105 steps to the

top,

we were able to see a magnificent view of the city. Despite its

reputation

as "the Tower of Death," Maksuma, our English-speaking guide, told us

that

only one person had been thrown from the top of the minaret.

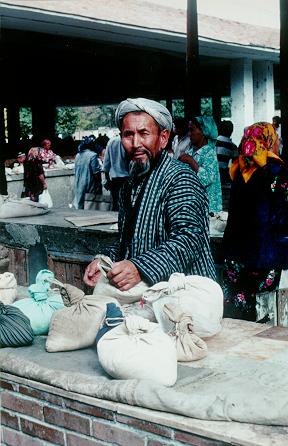

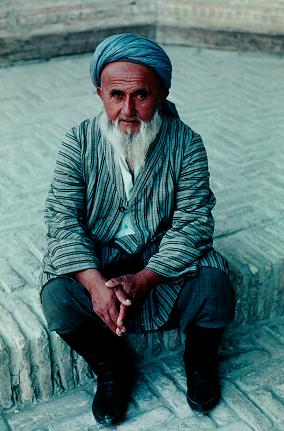

The

magnificent monuments of Bukhara are only part of the charm of the

city,

however. Equally as fascinating are its inhabitants, especially the

numerous

photogenic aqsaqals ("whitebeards"): old men in turbans,

quilted

striped coats (called chapans), and black leather boots, many

of

whom spend their days playing chess in front of the Lyabi-Khauz

Madrassah.

The

magnificent monuments of Bukhara are only part of the charm of the

city,

however. Equally as fascinating are its inhabitants, especially the

numerous

photogenic aqsaqals ("whitebeards"): old men in turbans,

quilted

striped coats (called chapans), and black leather boots, many

of

whom spend their days playing chess in front of the Lyabi-Khauz

Madrassah.

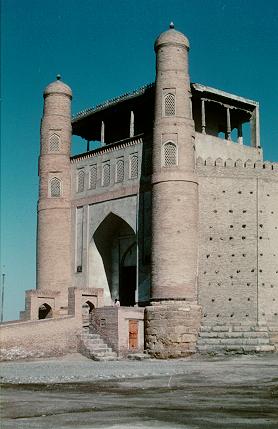

In

the northwest corner of the old city, the Ark (the former palace of the

Emir of Bukhara) contains a museum which gives a good overview of the

history

of Bukhara. Nearby, the Zindan (city jail) recreates the conditions of

nineteenth century Central Asian justice. It was here, in the Bug Pit

inhabited

by rats, cockroaches, lice, ticks and assorted other vermin, that the

hapless

British officers Stoddart and Conolly were held by the Emir until he

had

them executed in front of the Ark in 1842.

In

the northwest corner of the old city, the Ark (the former palace of the

Emir of Bukhara) contains a museum which gives a good overview of the

history

of Bukhara. Nearby, the Zindan (city jail) recreates the conditions of

nineteenth century Central Asian justice. It was here, in the Bug Pit

inhabited

by rats, cockroaches, lice, ticks and assorted other vermin, that the

hapless

British officers Stoddart and Conolly were held by the Emir until he

had

them executed in front of the Ark in 1842.

Located twenty minutes west of the city by bus or car is the shrine of Bahauddin Naqshaband, the founder of the Naqshabandi order of Sufis (Muslim mystics). Despite having served time as an anti-religious museum under the Soviets, the shrine continues to thrive and on most days, the imam (Muslim priest) who sits under the mulberry tree can be found dispensing prayers, spiritual remedies, and advice in exchange for a small fee.

After

several days in Bukhara and a short visit to the Ferghana Valley, the

agriculturally

rich northeast finger of Uzbekistan, we returned to Tashkent for our

final

few days in the country. On our last day in the capital, I observed a

scene

which seems to be a fitting metaphor for contemporary Uzbekistan. High

above the crowd at an outdoor market, a tightrope walker nimbly walked

and then ran across a wire stretched between two supports. As he

successfully

negotiated his way along the high wire, I thought about how Uzbekistan

too is walking a tightrope, seeking to balance the pull of the West

with

the inertia of tradition. Hopefully, the country will be able to keep

its

balance as well as the young boy on the high wire was able to.

After

several days in Bukhara and a short visit to the Ferghana Valley, the

agriculturally

rich northeast finger of Uzbekistan, we returned to Tashkent for our

final

few days in the country. On our last day in the capital, I observed a

scene

which seems to be a fitting metaphor for contemporary Uzbekistan. High

above the crowd at an outdoor market, a tightrope walker nimbly walked

and then ran across a wire stretched between two supports. As he

successfully

negotiated his way along the high wire, I thought about how Uzbekistan

too is walking a tightrope, seeking to balance the pull of the West

with

the inertia of tradition. Hopefully, the country will be able to keep

its

balance as well as the young boy on the high wire was able to.

![]()

SHOTS: Tetanus/diphtheria, typhoid, and Hepatitis A as a minimum. If you plan to be in the south, consider chloroquine pills as a precaution against malaria.

GETTING THERE: A number of major airlines fly to Tashkent, including Lufthansa, Turkish Airways, Air India, and Pakistan International Airlines. Uzbekistan Havo Yollari (Uzbekistan Airways) connects Tashkent to over a dozen European, Middle Eastern and Asian cities. Consult your travel agent. There is a $10 US/person airport tax when leaving Tashkent Airport.

GETTING AROUND: In Tashkent, the Metro (underground) is quick, clean, and inexpensive, costing about one or two cents per trip. The bus and trolley system in Tashkent is very efficient and city maps show all the routes. If you are traveling by bus or train, take your passport and visa to the OVIR (the Uzbek version of the KGB) in the station to get your travel plans approved. Be prepared for long waits in the ticket lineups. The nicest train in the country is the Altin Wadi ("Golden Valley") which runs from Tashkent to Andijan in the Ferghana Valley.

WHERE TO STAY: Some of the larger and more prestigious hotels can cost you as much as $120 US/night for a double room. Most hotels are much cheaper. In Samarkand, try the Hotel Sayor (opposite the SUM store, near the train station) or the Hotel Saikal (on Sharaf Rashidov Street). In Bukhara, try Mubinjon’s B&B, Ichoni-Pir, Stadionya Str. 4 (phone: 011-7-36522-420-05) or Sasha & Lena’s B&B, 13 Molodioshnaya (phone: 011-7-36522-338-90). For more detailed information on accommodation, see Central Asia: The Practical Handbook, by Giles Whittell (Cadogan Books, 1993).

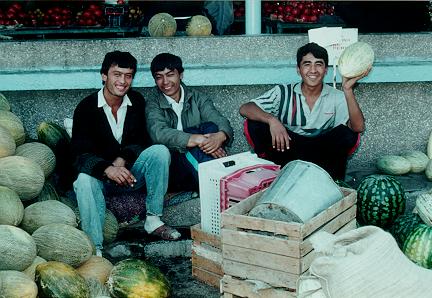

WHERE TO EAT: Uzbek food is tasty, but not overly spicy. There is usually an abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables available in the outdoor markets, as well as meat, nuts, and dairy products. Fruits and vegetables should be washed thoroughly before eating. Many roadside stands sell shashlik (shishkebabs) or palau (rice pilaf). In general, if the food is hot, it is okay to eat. It is not customary to tip in a restaurant or a tea shop. The most authentic eating experiences can be found in the small chaikhanas (tea shops) that abound in every city in Uzbekistan. Do not drink unboiled water; tea and Coke are always available. If you are fortunate enough to be invited to join an Uzbek family for a meal, you will be offered a sumptuous spread, including palau, nan (bread), fruits, tea, and vodka.

TOURS: To arrange tours in the country, contact Raisa Gareyeva, the director of Raisa and Associates, Salom Travel, Prospect Navoi, Bldg. II, Apt. 61, Bukhara, Uzbekistan (phone and fax: 011-7-3652-237277, email: [email protected]).

MONEY: In general, Uzbekistan has a "cash only" economy. Only a very few stores and hotels in Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara take credit cards. Travelers’ Checks are unknown and cannot be cashed. Although American dollars, British pounds, and German marks can be changed at most banks, the US greenback is the only money which talks in Uzbekistan. Make sure your bills are clean, not written on, too old, or too wrinkled. You can change money either at a bank (rates vary, so check around) or in the market (where a higher rate is offered, but there may be risks involved). Carry cash in a money belt; although it is not a common occurrence, beware of pickpockets, especially on public transit.

COSTS: Kebabs and tea for two in a tea shop: $1; dinner for two in a nice restaurant: $4; bus from Tashkent to Samarkand for two: $6; train from Bukhara to Ferghana for two: $5; taxi ride in a city: $1; museum entrance fee for two: $1-$2; atlas silk fabric: $1.50/meter; silk table cloth: $4. In general, prices in the bazaar are usually cheaper than they are in the stores (bazaar prices are flexible, whereas store prices are fixed), but shop around to make sure you aren’t being charged "tourist prices." In the market, it is generally acceptable to bargain before buying something. If you pay in dollars, you will pay more than you would in som.

LANGUAGE: Almost all residents of Uzbekistan speak either Russian or Uzbek. If you can speak Russian, you will be able to get around without too many problems, but if you can learn some Uzbek, you will certainly endear yourself to the Uzbeks. A few Uzbeks, mostly young people, can speak some English, since they study it in school. Currently, Uzbek is written in the Cyrillic alphabet that is used for Russian. However, like the rest of the Central Asian republics, Uzbekistan is in the process of switching over to a modified Latin script, similar to that used in Turkey. Colloquial Uzbek, a four hour cassette course, is available from Audio Forum, 96 Broad St., Guilford, Conn. 06437.

PHONES: The moral of the story with phones in Uzbekistan is "If at first you don’t succeed, try again." Phones can go dead, dial a wrong number, or give a busy signal when the number is not busy. To make a long distance call within the former USSR, first dial 8 and then wait for the dial tone. To call overseas, dial 8 followed by 10. Uzbekistan shares the same country code with the rest of the former USSR: 7. City codes within Uzbekistan are as follows: Bukhara (36522), Ferghana (3732), Urgench-Khiva (36222), Samarkand (3662), and Tashkent (3712).

WEATHER: The best times of the year are the spring and the fall, when temperatures are neither too hot nor too cold. January and February are the coldest months. June and July are unbearably hot. May and September are probably the most pleasant months of the year.

WHAT TO TAKE: suitcases, not backpacks; Central Asia: The Practical Handbook, by Giles Whittell (Cadogan Books, 1993); comfortable walking shoes; a pocket photo album (makes a great conversation starter if you get invited into an Uzbek home for a meal); disposable syringes with a note from your doctor (in case you need to go to hospital for any reason); a portable water filter and water purification tablets; voltage converter (Uzbekistan uses 220/240 volts).

WHAT TO WEAR: Dress conservatively, due to Uzbekistan’s Muslim culture. Tashkent is becoming increasingly less traditional, but tradition still rules in the countryside and some of the smaller urban centers. In Tashkent, most Western clothing is acceptable, but you should still dress modestly. Outside of Tashkent, the following guidelines should be followed: neither men nor women should wear shorts, and women should not wear skirts or dresses above the knee, pants, or sleeveless tops. Low necklines are a definite no-no everywhere in Uzbekistan.

EMBASSIES: The American Embassy is located at 82

Chilanzarskaya

in Tashkent, phone: (3712) 77-14-07 or 77-11-32.

| Oxus Central Asia Page | Oxus Home Page |

![]()